Last Updated on November 5, 2021 – 7:51 am

Several studies reveal that employee-manager relationships are a significant factor in employee development. A LinkedIn Learning study found that employees see “manager direction” as the biggest motivator for developing themselves. Fifty-six percent of employees say that they would spend more time learning and developing if their managers directed them to improve their skills. An academic study found leader’s certain behaviors stimulate engagement in learning and developing activities.

Whether you are a small firm or a multinational corporation, an effective communication system should always include employee development conversations. It’s a matter of being present and transforming a conversation into something that makes a difference for everyone. Yet, most managers have a hard time guiding their employees. In a study at the University of London, researchers asked 104 people to discuss significant career development discussions they had in their careers. Only 21 percent of the conversations were with a boss. So, how can we get the most out of our development conversations? Let’s look at some of the best examples and great techniques.

1. Split Growth Dialogs from Performance Evaluations

Development conversations, as one interviewee noted in Journey’s study, are mostly “seen as the step-child of performance reviews.” The major problem with performance management systems today is that when managers sit down to give employees their annual review and salary increase, the employees focus on the extrinsic reward -a raise, a higher rating- and learning shuts down. As Prasad Setty, VP of People Operations at Google, explains, “Traditional performance management systems make a big mistake. They combine two things that should be completely separate: performance evaluation and people development. Evaluation is necessary to distribute finite resources, like salary increases or bonus dollars. Development is just as necessary, so people grow and improve.”

2. Development conversations Begin with Trust

In the same study at the University of London, “the researchers asked people to discuss what made the development conversations so effective. Interestingly, people did not talk about what the manager/coach did. Instead, they talked about the person’s character. They said the conversations are valuable because the other person was honest, frank, nonjudgemental, and had their best interests at heart. They valued someone who cared about them and was willing to push them hard.” states Yost and Plunket in their book Real-Time Leadership Development. A study revealed that when employee development discussions between employees and their supervisors were perceived to be fair, it positively affected goal commitment, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction.

3. Different People Will Have Different Needs at Different Times

The same person can have a different need at different times, or different people may have different needs at the same time. So, we have to define a framework. In their book Real Time Leadership Development, Paul R. Yost and Mary Mannion Plunkett say, “Conversations that happen at four points during an employee’s career are particularly important catalysts for development: job transitions, ongoing coaching, confronting performance problems, and career development conversations.” Let’s have a quick look at them one by one.

-

- Job transitions: People are more open to learning and feedback during times of job transitions. The manager’s role is critical in defining the responsibilities and expectations. The manager should also provide feedback and create psychological safety where transitioning employees can ask “stupid” questions.

-

- Ongoing coaching: Ongoing guidance, support, and advice that leaders provide to their direct reports are also critical in continuous development. Good managers can push their people to be their best with coaching conversations. Two academicians identified three key factors in coaching: guidance, facilitation, and inspiration.

-

- Confronting performance problems: “Dealing with performance problems can be one of the hardest when it comes to development conversations, but they can also make a real difference in someone’s career,” states Yost and Plunkett.

-

- Career development conversations: These meetings are focused on the person’s long-term career goals. Managers can discuss where the person’s talents can be used, areas of future development, weaknesses that are being overlooked, and strengths that the person doesn’t even realize they have. The discussions should end with action items and a follow-up meeting.

For the book, First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently, Gallup interviewed managers to see if they have a “performance management” routine in these contexts. Although each manager’s routine was different, reflecting their unique style, they found four characteristics common to these great managers: First, the routine is simple. Great managers prefer a simple format that allows them to concentrate on what truly matters: what to say to each employee and how to say it at a certain point in their career. Second, the routine forces frequent interaction between the manager and the employee (we’ll come to that in a short while). Third, the routine is focused on the future. And last, the routine asks the employee to keep track of her/his performance and learnings. This way, employees aren’t passive observers but have a say and active role in their development at any point in their career.

4. Make Ongoing Development Conversations a Part of Your Culture

Development conversations can happen any time: during ongoing project discussions, over lunch, or in a hallway, as in formal 1:1 meetings. Yet, structured development meetings have the most significant impact. According to Journey’s employee development study, infrequent development discussions constitute a substantial hurdle in employee growth. Most companies ask their managers and direct reports to discuss growth in performance reviews conducted once or twice a year. They start by evaluating performance and then continue with growth. Development conversation is a step-child in this model. As one interviewee noted, “This happens every time. We complete an IDP form with my manager in a rush. A year passes. And I realize, just before our review, that I (and my manager, of course) totally forget what we are developing.”

Journey app piloted annually, bi-annually, quarterly, and monthly development 1:1s. User feedback and analysis indicated that quarterly meetings are the most effective one: not too far away to forget development and not too time-consuming to give away.

Feedback is also a major part of ongoing people development. Yet, studies show that one-third of the time, feedback led to lower performance. Thus, it is important to know what makes feedback most effective. Studies suggest that effective feedback should be timely, structured, explorative, informative, contingent, focused on the topic not the person, and future-focused. Check this video to learn more about giving effective feedback.

To sum up, managers shouldn’t rely on one conversation a year to discuss the employee’s development. Real development is a part of an ongoing process. Real development is a journey.

5. Using a Guide or a Framework Always Helps

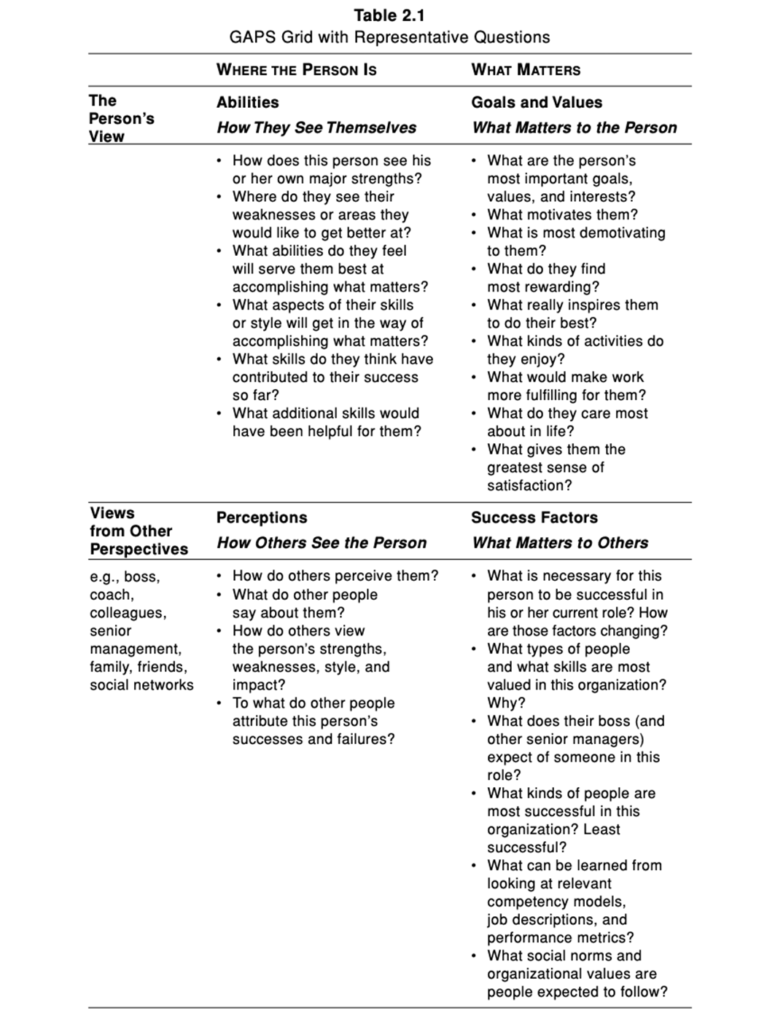

Using a guide or a framework such as the GAPS Grid will help structure a development conversation. GAPS Grid refers to:

-

- Goals and Values (what motivates the person’s behavior),

-

- Abilities (a person’s view of her/his skills),

-

- Perceptions (how others see the person),

-

- Success Factors (expectations of others regarding what it takes to be successful in a given role).

In their book Performance Management: Putting Research into Action, Smither and London advise beginning the development conversation with a discussion of the person’s Goals and Values. It shows a genuine interest of the leader to the employee, clarifies the person’s motivation. The second part of the conversation should explore the relevant Success Factors for a current/desired role. A discussion of Abilities and Perceptions follows this to determine where development will have the greatest impact on a person’s goals. Remember, “a common mistake in both conversations is starting with feedback (perceptions data). It is much more effective to specify the objectives first (accomplishing more of what matters to one or both parties (Goals, Values and Success Factors) and then discuss how each party views the person relative to those objectives (Abilities and Perceptions). See Table 1 below to have a closer look at the GAPS Grid.

You can see the representative questions/concepts related to where the person is now on the left-hand column. The right-hand column focuses on what matters most. Both issues are considered from the person’s perspective on the top row and from the perspective of any significant others, such as bosses, senior management, people whom the person directly reports to, colleagues, the leader/coach, and family on the bottom row.

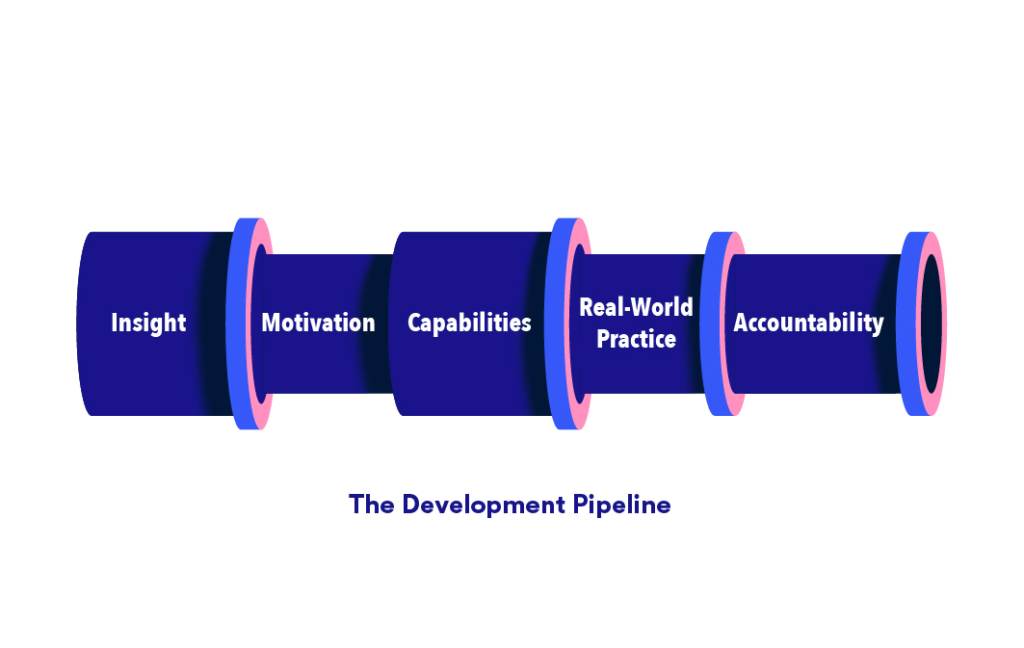

6. Let Them Focus on One Topic at a Time

Several studies show when people set multiple development areas to improve, they have difficulties focusing. But, when they select only one topic for a specific period, it is easier to focus and develop. Laszlo Bock, former Chief HR Officer of Google, mentions the benefits of simplification in his book, “If people have just one thing to focus on, they’d be more likely to achieve genuine change than if they divided their efforts.”

While a development plan with 20 critical issues to address win points for comprehensiveness will not motivate a person to create disciplined action. “Most of us, if we are lucky, can work on a maximum of one or two things at a time. We can agree to ‘lose weight,’ improve our disposition,’ ask questions rather than tell people,’ ‘delegate responsibility and authority.’ But chances are we are incapable of doing all of them at once.” states Stringer and Cheloha in The Power of a Development Plan. Journey app limits managers and team members to select only one development area every three months while creating development plans.

Less is more, even for peer feedback. Laszlo Bock wrote in his book how they changed their approach. “In 2013, we experimented with making our peer feedback templates more specific. Prior to that, we’d had the same format for many years: List three to five things the person does well; list three to five things they can do better. Now we asked for one single thing the person should do more of, and one thing they could do differently to have more impact. We reasoned that if people had just one thing to focus on, they’d be more likely to achieve genuine change than if they divided their efforts.”

All development conversations require your full presence. “Ask whether they are motivated by what they are working on, where they see themselves going next, and if there’s anything on their mind that they want to discuss.” Remember, this journey has a two-way road.

You can see additional resources on employee development and onboarding below.

Leave A Comment